Agro-climatic postharvest risk warning maps info

Postharvest losses (PHL) can occur at each stage along the postharvest value chain, from harvesting to storage and marketing. For example, some of the crop may get left behind in the field, spilt during transportation, or attacked by fungi, insects or rodents during harvesting, drying or storage. All of these can reduce the quantity or quality of food available and the associated income opportunities for food producing households and nations. The postharvest loss (PHL) of food crops, during or after harvest, is a loss of valuable food and of the inputs required to produce and distribute it. The causes of PHL and the stages at which they occur are numerous and varied depending on the crop, the agro-climatic conditions and a variety of other factors and contexts.

Changes in temperature, rainfall, humidity and extreme weather events affect postharvest systems and the associated loss-causing-factors – such as insects, fungi, handling, transport and storage durations, conditions and methods – as well as the natural and human responses to these climatic changes. Review and discussion of the impacts of climatic factors and changing climates on postharvest agriculture with a focus on staple cereals in sub-Saharan Africa is provided by Stathers et al. 2013.

Given the relationships between agro-climatic factors and the causal organisms of postharvest losses, models can be developed using agro-climatic data to produce risk warnings of factors which cause postharvest biodeterioration in quality or quantity. The following text describes a risk warning model developed by Felix Rembold as part of the African Postharvest Losses Information System (APHLIS) for providing province-level agro-climatic-based mycotoxin risk warnings across sub-Saharan Africa.

What are mycotoxins?

Mycotoxins are major food and feed contaminants affecting global food safety and food security, especially in low and middle-income countries. Mycotoxins are poisonous chemicals produced by certain fungi which are able to grow on a wide range of commodities. While aflatoxins are probably the most well known and intensively researched mycotoxins, many different mycotoxins exist, with over 400 different mycotoxins reported to date.

Fungal contamination and growth can occur in crops during the in-field production stages, or during the handling, drying, storage, transportation, processing, or marketing of the commodities. Such contamination causes a major loss in the quality of the crop and can be a major food safety issue. Mycotoxins are invisible to the naked eye. Although removing mouldy grains contaminated with funghi before storing, selling or eating them can help limit the risk of humans or livestock consuming mycotoxins, even clean and healthy looking cereal and legumes grains as well as many other crops can have dangerous levels of mycotoxins.

Mycotoxins are a world-wide problem, but to date they are more frequently encountered in the tropics. In Africa in particular, mycotoxin contamination remains a major source of concern, with adverse effects not only on human health and nutrition, and animal productivity but also on commodity trade and on the economy in general.

The consumption of mycotoxin-contaminated food or feed can affect human and animal health and can have severe health consequences. For example, chronic exposure to aflatoxins can cause an increase in liver cancer rates, a negative impact on nutrition resulting in a higher prevalence of stunting and impaired cognitive development in children, and lowered immunity. Acute poisoning from aflatoxins is rare but very serious, affecting digestion and leading to oedema, lethargy, blindness and potentially death.

High temperature, extreme weather conditions (drought, heavy rainfall), moisture content and pest presence are among the factors that facilitate the presence of fungi and the production of mycotoxins. Climate change and the increased occurrence of climate extremes make mycotoxin contamination prevention more challenging. The impacts of different climate change scenarios, cultivars and planting dates on projected aflatoxin contamination risk in Malawi's maize crop in 2035 and 2055 for each of the three regions of the country were modelled by Warnatzsch et al. 2020.

To find out more about mycotoxins see Ayalew et al., 2016; Udomkun et al., 2017; Gbashi et al., 2018.

Agro-climatic postharvest risk warning maps info

Meaning of climate information for mycotoxin risk warning

Fungal growth on maize cobs being sun-dried in Malawi. Mycotoxins are invisible. Although removing mouldy grains before storing, selling or eating them can help limit the risk of humans or livestock consuming mycotoxins, even clean and healthy looking cereal and legume grains as well as many other crops can have dangerous levels of mycotoxins. For several crops including maize and groundnuts, the development of Aspergillus flavus and other mycotoxic fungi during the pre- and post- harvest stages is largely weather-driven. For example, drought stress during certain stages of plant growth can increase the risk of pre-harvest fungal contamination of the crop, and can enhance the production of mycotoxins and thus the contamination of the food crop. Unusually abundant rainfall just prior to harvest or during crop drying, also favour the growth of and infection by various fungi. This contamination passes along the food chain and would usually only become apparent during testing of the crop postharvest.

Several agricultural and food security early warning systems are monitoring both drought stress and excess rainfall, suggesting the possibility of using their evidence for mapping weather conditions which can increase the risk of mycotoxin contamination. This allows the production of agro-climatic mycotoxin risk maps to provide early warning information of possible elevated mycotoxin contamination risk and for guiding targeted contamination testing and risk-mitigation measures.

For maize, several crop growth models have been used for predicting aflatoxin contamination, including those by Chuahan et al. in 2010 and by Battilani et al. in 2014. Those studies evidenced an increased risk of aflatoxin contamination linked to water stress during the grain filling stage for certain temperature windows. This relationship was field tested in Australia and in Kenya (Chuahan et al., 2015). In semi-arid and tropical climates in Africa, the temperature window can be assumed to be ideal for mycotoxin development during most of the year, suggesting a need to focus mainly on humidity levels during pre- and post-harvest stages.

To make agro-climatic mycotoxin risk warnings available in APHLIS, it is assumed that the relationships described above between crop stress factors such as drought and excessive rainfall and mycotoxin contamination, that have been tested under laboratory and localized field conditions, remain valid at different spatial scales and for major crops at the province or country level. Ignoring the climatic variability among the different areas of a province, as well as non climatic factors, is certainly a major approximation, but it is believed that making available climate-based mycotoxin risk early warnings at province level is relevant for allowing more detailed monitoring and for guiding field surveys. This information is expected to be useful for agricultural and food safety analysts at the province or country level, while it is most likely too broad for working at the farm level.

Simple agro-climatic modelling of mycotoxin risk based on ASAP (Anomaly hotSpots of Agricultural Production) data

ASAP (Anomaly hotSpots of Agricultural Production) is an agricultural early warning system that provides drought condition warnings for food insecure areas in the world, based on 10-daily updates of climate and biophysical data coming from from Earth Observation and weather models. The ASAP system monitors weather and biophysical indicators anomalies for agricultural areas (all crops), but cannot provide crop specific information, since at the global scale, detailed crop type maps are not available. A simple model was developed to use pre-harvest drought anomalies and excessive rainfall around harvest anomalies from the ASAP system to model agro-climatic mycotoxin risk and map it every 10 days for the APHLIS website.

The maps shown by APHLIS use the same phenological model as the ASAP system which is based on remote sensing analysis of a time series of normalised difference vegetation index (NDVI) data. The mean annual development cycle of all crops in a province is divided into three stages, vegetative (NDVI going from 25% to maximum), maturation (NDVI from maximum to 75%) and senescence (NDVI decreasing and below 75%). Although this phenology is not crop specific and its phases are relatively broad, as compared to real phenological observations, we can assume for example that maize flowering occurs in proximity of the maximum NDVI and that the grain filling stage, which starts shortly after flowering, will in many situations fall into the ASAP phase called “maturation”. This leads to the possibility of using all ASAP agricultural drought warnings occurring during the maturation phase as climate-based mycotoxin risk warnings (for more detailed information on the ASAP warning system refer to Meroni et al. 2019).

Unusually abundant rainfall prior to or around harvesting is another climate factor generally associated with increased mycotoxin contamination risk due to higher moisture content of grain at harvest. Rainfall data for the whole African continent are available from many sources and are generally estimated based either on satellite data or atmospheric circulation models, because of the low density of rain gauges reporting in near real time across most African countries. At the same time, data availability about actual harvesting time is very scarce and cannot easily be derived from satellite data. This means that again some approximation is necessary for using a simple model of increased rainfall frequency and abnormal amounts prior to harvest. In particular the rainfall anomaly indicator SPI1 (standardized precipitation index for monthly rainfall) can be used as indicator for abnormally abundant rainfall, if we can identify the month prior to harvest. As for the pre-harvest drought indicators, ASAP phenology can also be used for identifying the month prior to harvest. The senescence stage (NDVI<75% of its maximum annual value) is close to the end of the crop season and can therefore be used as a time window that approximates the period around harvest. We use SPI1 (1 month) anomalies (i.e. when SPI1 for more than 25% of the agricultural area of a province is above 1.5) as an indicator of increased risk of mycotoxin contamination due to abnormal amounts of rainfall. This corresponds to the statistical probability that the monthly rainfall falling around harvest is part of 6.7% of the largest rainfall amounts over the whole time series. Areas with no or little rainfall around harvest are not mapped as risk areas.

Modelling historical mycotoxin risk frequency

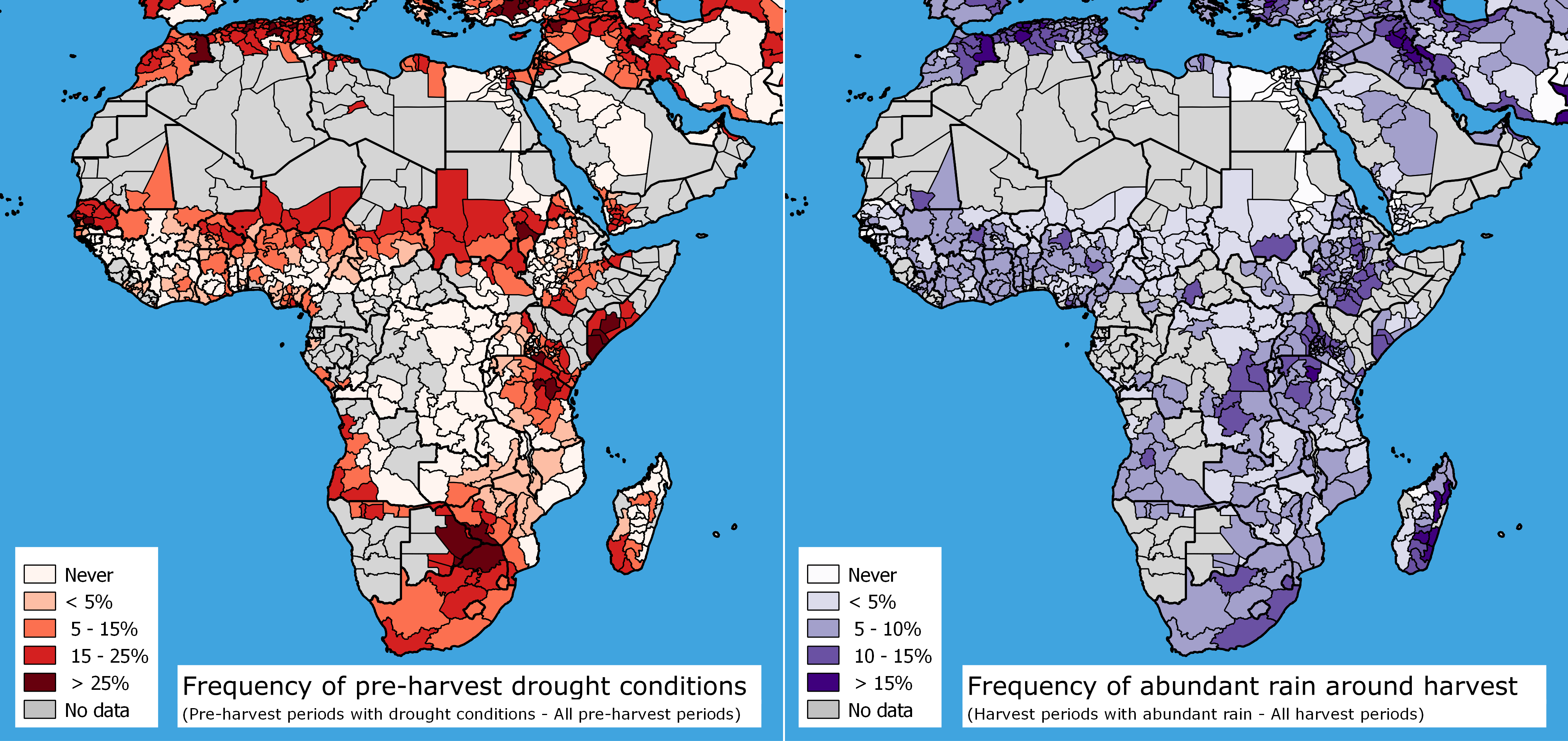

The maps show — for each province — the percentage of 10-day periods (over the years from 2004 to 2019), that crops were likely to be subject to increased mycotoxin risk due to either: pre-harvest drought conditions during maturation (left) or abundant rainfall around harvest (right). (Image: APHLIS)

The maps show — for each province — the percentage of 10-day periods (over the years from 2004 to 2019), that crops were likely to be subject to increased mycotoxin risk due to either: pre-harvest drought conditions during maturation (left) or abundant rainfall around harvest (right). (Image: APHLIS)

Based on the full time series of ASAP data, for both pre-harvest drought and unusually abundant rainfall around harvest, historical mycotoxin risk maps have been calculated for the past 15 years. These maps give an idea of the mean percentage of crop growth time which is characterized by increased agro-climatic mycotoxin risk for each province in Africa, showing which areas can be considered most sensitive to the problem. As explained previously, this does not necessarily imply that final mycotoxin occurrence is highest in those areas, since the actual occurrence of mycotoxins depends on many other factors including farming practices, intra province level variability and other agro-ecological parameters not taken into account by this simple model.

References

Ayalew, A., Hoffman, V., Lindahl, J. & Ezekiel, C.N. (2016). The role of mycotoxin contamination in nutrition: the aflatoxin story. In: Achieving a nutrition revolution for Africa: the road to healthier diets and optimal nutrition. (Eds. N. Covic, S. L., Hendriks). Chapter 8. pp 98-114. Washington D.C.: IFPRI. http://dx.doi.org/10.2499/9780896295933_08

Battilani, P., & Leggieri, M. C. (2014). Predictive modelling of aflatoxin contamination to support maize chain management. World Mycotoxin Journal. http://doi.org/10.3920/wmj2014.1740

Chauhan, Y. S., Wright, G. C., Rachaputi, R. C. N., Holzworth, D., Broome, A., Krosch, S., & Robertson, M. J. (2010). Application of a model to assess aflatoxin risk in peanuts. Journal of Agricultural Science, 148(3), 341–351. http://doi.org/10.1017/S002185961000002X

Chauhan, Y., Tatnell, J., Krosch, S., Karanja, J., Gnonlonfin, B., Wanjuki, I., & Harvey, J. (2015). An improved simulation model to predict pre-harvest aflatoxin risk in maize. Field Crops Research, 178, 91–99. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2015.03.024

Gbashi, S., Madala, N.E., De Saeger, S., De Boevre, M., Adekoya, I., Adebo, O.A., Njobeh, P.B. (2018). The socio-economic impact of mycotoxin contamination in Africa. In: Mycotoxins – Impact and Management Strategies. (Eds. P.B. Njobeh & F. Stepman). DOI: 10.5772/intechopen.79328

Meroni, M., Rembold, F., Urbano, F., Csak, G., Lemoine, G., Kerdiles, H., Perez-Hoyoz, A. (2019). The warning classification scheme of ASAP – Anomaly hot Spots of Agricultural Production, v3.0, doi:10.2760/798528 https://mars.jrc.ec.europa.eu/asap/files/asap_warning_classification_v_3_1.pdf

Stathers, T., Lamboll, R. & Mvumi, B.M. (2013). Postharvest agriculture in changing climates: its importance to African smallholder farmers. Food Security, 5(3): 361-392. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-013-0262-z

Udomkun, P., Wiredu, A.N., Nagle, M., Bandyopadhyay, R., Müller, J., Vanlauwe, B. (2017). Mycotoxins in Sub-Saharan Africa: Present situation, socio-economic impact, awareness, and outlook. Food Control, 72(A): 110-122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2016.07.039

Warnatzsch, E.A., Reat, D.S., Camardo Leggieri, M. & Battilani, P. (2020). Climate change impact on aflatoxin contamination risk in Malawi's maize crop. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 4. DOI:10.3389/fsufs.2020.591792